Early and Late Career Collaboration #2: Why Family Medicine?

Published April 15, 2024 Progress Notes 2 CommentsHere is our second view from our opposite vantage points. You can read more by Lilian White on her own Substack:

https://open.substack.com/pub/learningmedicine/p/ms8?r=254ice&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

Why Family Medicine? (By Hans)

I knew from age 4 that I wanted to be a doctor. At that point in my life I had been seen at home once or maybe more by a general practitioner who did housecalls. I had also been hospitalized with abdominal pain. I remember riding up in the elevator, teddy bear in hand, to the x-ray department for testing. Starting at age 6, I had yearly eye doctor visits, most of them with an older doctor who practiced in a 1920’s apartment next to his own living quarters. I remember his slow, methodical examinations and his persistent concern for the worsening severity of my nearsightedness.

In high school I pictured myself as a general practitioner, in Swedish ALLMÄNLÄKARE. Läkare, our word for physician, literally means healer and the prefix, allmän, means general. But having had all that exposure to ophthalmology and also being interested in photography, including darkroom work, I started to think that maybe I wanted to be an eye doctor.

As an exchange student in America, I sat on the living room shag carpet in front of my host family’s Zenith console TV and watched Marcus Welby every week. That, along with my general infatuation with America, grew into a vision of being a general practitioner here. The term Family Practice (now Family Medicine) and the residency requirement to hang out your shingle had just come about and wasn’t all that well known. The first certifications in the new specialty, Family Practice, actually happened around the same time I spent my senior year here.

After high school and my military service, I applied to only one medical school, Uppsala University. I knew my grade point average should get me in. (Sweden’s high school is tougher than here and medical school is longer, so there is no general 4 year college between.)

During the six month wait for medical school acceptance and start date, I worked as a substitute teacher. From second grade to eleventh, definitely easier in the lower grades, I totally enjoyed seeing kids learning and making connections about how the world works. For a fleeting moment, I thought, “what if I don’t get accepted to Uppsala”, but reassured myself that I could keep subbing until I got in somewhere else.

In medical school at Uppsala, I found I enjoyed all the clinical subjects and rotations and very early on I took a liking to psychiatry and I saw how it intersected with so many of the other specialties. In my ophthalmology rotation I learned that people with high grade myopia, nearsightedness, often have a higher risk for retinal detachments. That made me decide that I didn’t want to risk being a visually impaired eye doctor.

Things really helped me make up my mind when, as the regulations worked in Sweden at least back then, halfway through the clinical years of our 5 1/2 year curriculum, I moonlighted many weekends seeing urgent care patients right next to the “real” emergency room. My shift lasted from early Friday evening to early Monday morning. I loved it, and because the ER was right next door, I never felt intimidated by the cases I saw.

To this day, I enjoy the variety of seeing both rare and common conditions (like Marcus Welby) coupled with a feeling of satisfaction when I can explain things (like a teacher) so that patients feel reassured and empowered to deal with their disease, even when most or all of their problems are psychological in nature. (I am often the only doctor around that is comfortable with psychopharmacology.)

Family Medicine suits my temperament. It keeps me curious to learn, connected with my patients and allows me to have a broad view. It lets me look for the big picture, rather than wear blinders and saying, “that’s not my department”.

Why Family Medicine? (By Lilian)

Some decisions in life are clear – a distinct, well-defined moment in time.

Others are born from a slower, more gradual coming to the light.

In either case, the ending is the same.

But the journey to the decision impacts us along the way. This is the story of my decision to become a family doctor.

.

As a new medical student, I remember meeting all my similarly bright-eyed and bushy-tailed classmates for the first time. We gathered in the big auditorium, waving hello and learning names.

A question hung in the air, sometimes spoken, sometimes implied:

“What specialty are you planning to go into?”

A future part of our identities was already beginning to take shape.

I had thought at the time I would become a pediatrician. I loved being around children and had spent a summer as a camp counselor and later worked as a daycare assistant in college. I thought it would suit my personality, which seemed as good a reason as any. However, a wise faculty physician at the school strongly encouraged us all to attend a variety of specialty interest group meetings and to keep an open mind about what we might learn. So, like many M1s, I often stayed after class to listen to the different meetings. The free dinners didn’t hurt, either.

I distinctly recall the first family medicine interest group meeting I attended. Dr. Kate Conway shared her love of family medicine and the breadth of what a family doctor could do. And I fell in love with the family medicine myself. How everyone didn’t leave that room a family doctor wanna-be, I’m not sure. I knew I had found my people.

The conviction of my decision only grew during my time spent with another family physician, Dr. A. Patrick Jonas (whom I wrote about more here). I became enamored with everything family medicine, borrowing book after book from the packed shelves of his office. The personal, continuous patient-physician relationship fascinated me. I loved the idea of caring for whole families. Caring for children AND their parents felt a little like cheating when it came to addressing concerns in childhood. The undifferentiated complaint (e.g. cough, abdominal pain, etc.) became a puzzle to be solved. I loved the thought of being the first point of contact for my future patients – someone they could go to and trust with their concerns.

Dr. Skip Leeds, another influential family physician, taught me the value of family medicine in academia and research as we dove into projects on developing a differential diagnosis using metacognitive techniques. Who better to teach the skill of differential diagnosis than a physician who may care for any patient with any complaint? The family doctor may or may not be the definitive point of care (some estimate we can definitively address up to 80% of a patient’s concerns); but regardless our larger role is to help guide them along the path closer to their “values, goals and dreams” as Dr. Jonas teaches.

In short, I was in awe.

The family physician was the quintessential doctor to me.

Did my dedication ever waiver?

Absolutely. There was a brief period during my 3rd year clinical rotations I thought I might become a surgeon. I enjoyed the precision, the high after a successful surgery. But after several weeks, I began to miss my conversations with the patients, the humans on the other side of the drape.

So this is the story of how I decided to become a family doctor. I appreciate my subspecialty colleagues greatly! And I love that rather than specializing in a body part or a particular procedural technique (both of which we need!), as a family doctor, I truly enjoy specializing in the general (read: broad, deep), personal knowledge of the human in front of me and how my medical knowledge may help them find healing or relief.

This continuous, sometimes quite intimate relationship is also what makes family medicine so challenging. As with any other committed relationship, it can be difficult at times for both patient and physician, to say the least! And yet, as one of my mentors recently gently reminded me, it’s also what makes being a family doctor so meaningful. As I’ve been getting to know my new panel of patients over the last few months, I’ve come to appreciate more and more the human center that is family medicine.

What a blessing to be a family doctor.

It feels like we are moving backwards!

(This is going up on my Substack tomorrow. Links to older posts on the same topic below.)

In the beginning of the opioid epidemic, pain became the fifth vital sign, and we all know what happened after that.

The prescribing guidelines became more restrictive. States and national authorities implemented dose limits. The monitoring of physician prescribing practices and the shaming of physicians who prescribe more opiates than their peers is systematic now.

A Country Doctor Writes: is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

And yet, even though opiates have fallen out of favor and many of the non-opiate pain medications have at least come under suspicion, if not downright gotten viewed as inappropriate, we are now required by CMS to make ongoing pain assessments.

Lyrica is a controlled substance, its sister drug gabapentin has become popular with substance abusers, Cymbalta can cause mania, amitriptyline is viewed as inappropriate for the elderly because of side effects, largely anticholinergic. Cyclobenzaprine falls in the same category and requires prior authorization over age 65 with many insurance companies. NSAIDs can cause gastrointestinal hemorrhages and kidney damage and Tylenol had its maximum dose recommendation reduced several years ago because of concerns for liver damage, and so on…

So if we screen for pain with positive findings, there is no obvious, easy and safe intervention to offer. Considering that this is a throw-in when patients are actually being seen for something else, this is a prime example of Pandora’s box.

The common sense approach to screening is that it should be done when there is an effective intervention that can be offered. CMS did not in the past recommend screening for depression, for example, unless mental health resources were readily available. They changed their mind on that. But, where I work in Northern Maine, most therapists have a one year waiting list or worse. And the dirty little secret about antidepressant medications is that they work about 30% of the time – about the same as placebo.

We are mandated to screen for pain with no easy treatment options. The foundation for pain management is largely cognitive behavioral therapy, which is hard to come by as a modality that requires special skill on the part of the behavioral health counselor.

As far as interventional pain management, lumbar steroids etc., the outcomes data is mixed.

So here we are, beginning a routine visit with a patient who scores positive for pain and depression. Meanwhile, their blood pressure, blood sugar or whatever is out of control. The medical provider’s internal egg timer is ticking. How can we best help this patient in the limited time we have available?

Thanks a lot, Uncle Sam…

My Latest Writing Project

A little while ago I offered to mentor a couple of young doctors and two signed up. One of them was Lilian White, MD, who is in her first year of practice. Tonight she and I each posted a collaboratively written post on our respective Substacks. They deal with a physician’s feelings when a patient decides to leave their care. I think we have stumbled on an interesting longer-term writing project from two family doctors at opposite ends of the career spectrum.

https://open.substack.com/pub/acdw/p/early-and-late-career-collaboration

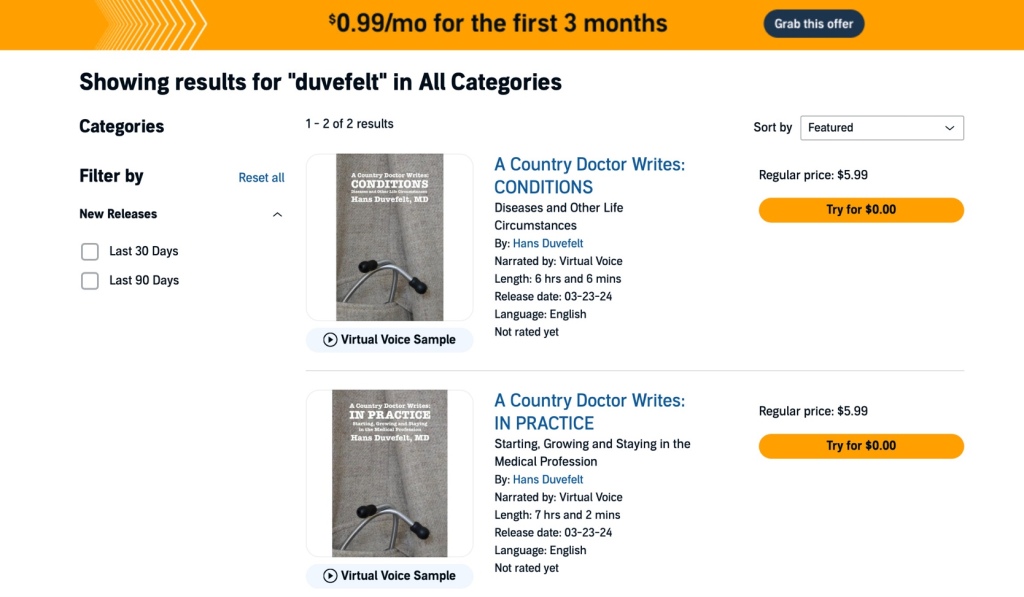

CONDITIONS and IN PRACTICE Now Available as Audiobooks

Published March 23, 2024 Progress Notes 1 CommentThis is exciting news! Early on after my two books were published, there were some comments asking me to record them as audiobooks. It sounded tempting, but more than a little daunting considering the possible distractions like cars driving by and dogs barking in the yard, so I ended up not doing it. Now, with the help of rapidly evolving AI generated narration, I have simply selected which of several voices I wanted to read my books, then clicked “Add audiobook with virtual voice”. That’s it. KDP (Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing) even promised to have the books ready and available on Audible in less than 72 hours. I have priced each at $5.99.

Both books are already live on Audible, an hour after I submitted them, and should be up on Amazon shortly.

WordPress Somehow Displays My Blog Posts Correctly Again With My Old, Retired Theme

Published March 22, 2024 Progress Notes 16 CommentsI thought I moved everything successfully to Substack. But I still get a lot of views here. Please comment below if you are still here , looking for new material and not moving to Substack. Thanks.