“I made myself a hypodermic injection of a triple dose of morphia and sank down on the couch in my consulting-room….I told her I was all right, all I wanted was twenty-four hours’ sleep, she was not to disturb me unless the house was on fire.”

– Axel Munthe, MD, The Story of San Michele (1929)

When people in this country mention the opioid epidemic, most of the time it is in the context of addiction with its ensuing criminality and social deprivation, and the focus is on opioids’ medical complications like withdrawal, overdose and death.

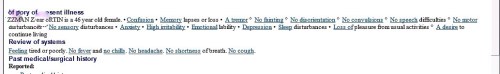

But that is only one of the opioid epidemics we have. Far greater is the epidemic of largely compliant patients who take their modest three or four daily doses of opiates for pain that was originally described as physical, but which in many cases is at least as much psychological – not imagined, in fact often quite severe, but nevertheless without a physical explanation or available cure.

Stimulation of opioid mu-receptors in the central nervous system induces euphoria more reliably than it reduces pain. In fact low dose opiates have been shown to sometimes lower pain thresholds but at the same time allowing dissociation from the pain experience.

People who smoked opium in antiquity didn’t all have intractable pain to begin with; many had miserable lives, just like many of my countrymen today with health problems, low income, poor education, lacking social supports and limited prospects for even a sustainable future in a job market they cannot even begin to qualify for.

Most physicians have or know of patients who have remained on the same moderate or low doses of opioids for many years and never failed a pill count or a urine test. They show no addictive behaviors, but without their prescriptions they function less well. We are still tapering most of them down or off their pain medications because that is what we do these days in response to the more famous opioid epidemic and in an effort to have fewer opioids, legal ones, that is, in circulation.

Ronald is a 57 year old patient of mine with a bad back, diabetic neuropathy and generalized anxiety disorder. He has been off his 5 mg oxycodone-acetaminophen (paracetamol) pills for two years now, takes pregabalin for his neuropathy and escitalopram for his anxiety with a low dose diazepam as needed. Since he came off his pain pills, his anxiety has been almost paralyzing. Social stressors, like a move to a different neighborhood, sent him into a frenzy. Then he fractured several ribs moving his washer and dryer up the icy front steps of his new home. The emergency room gave him just a couple of days worth of his old pain pills.

“It was amazing”, he explained to me, “I felt a warm wave travel through my body and it was like I was being hugged and everything felt all right, like I didn’t have a single thing to worry about in the whole world, even my nerve pain seemed like it didn’t bother me even though it was still there.”

Next, he asked if he could stay on them, “just three a day”.

I shook my head no.

He has his three other pills that don’t work as well. But at least they’re not opiates.