Acetylcysteine is an old drug with two major uses. Orally it can lessen liver toxicity from acetaminophen (paracetamol) overdose. Inhaled, it is a powerful mucolytic (loosens phlegm for people with lung disease).

I have a patient with severe lung disease who is on oxygen 24/7. She had been using high doses of guaifenesin, but still couldn’t raise her phlegm. I haven’t used it in many years but remembered from the early days of my career that acetylcysteine is a powerful mucolytic.

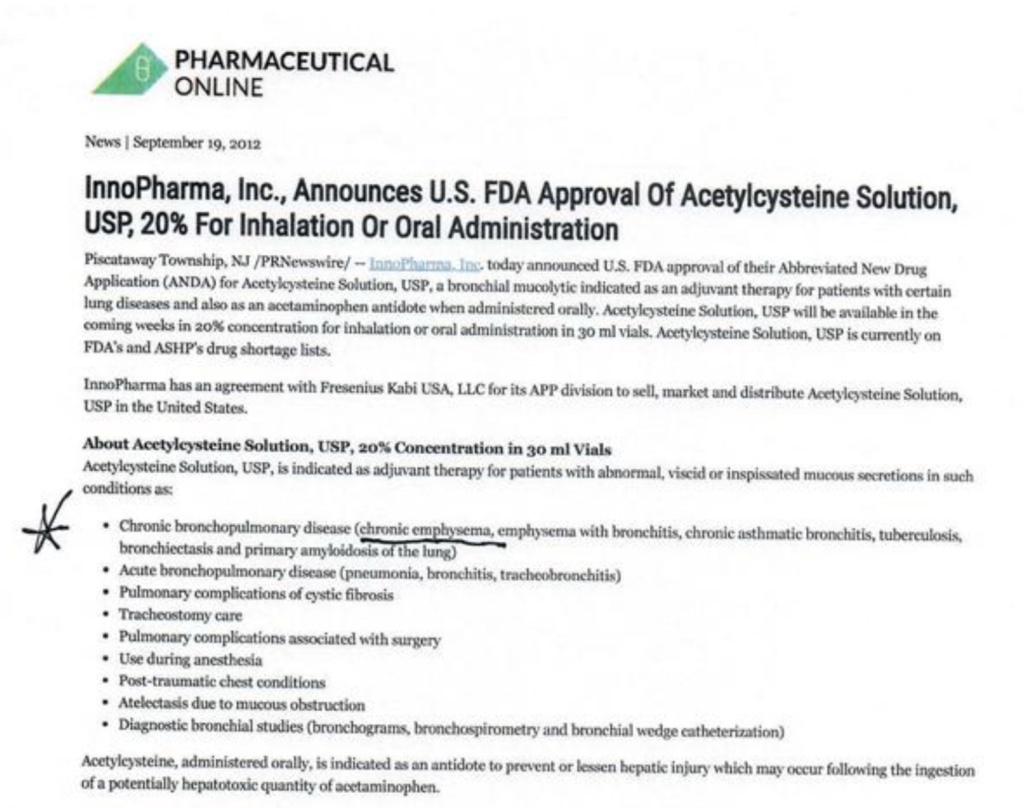

It’s used in the hospital more often than in outpatient care. So I called the patient’s pharmacy and they don’t have it in stock, but they can get it and my insurance would require a prior authorization. So I sent in a prior auth request with the diagnosis of chronic respiratory failure with hypoxemia. My application was denied. It said that the diagnosis I gave them was not a qualifying diagnosis. They were kind enough to reference a website I could go to to see what might qualify. So I did. There, I saw that emphysema qualifies. Well, darn it, She has had a CAT scan of her lungs showing severe emphysema, but in my book respiratory failure with low oxygen is a more severe diagnosis than emphysema. This is one instance where I sort of wish that AI would be used. The insurance companies deny requests because there’s no common sense in the process. They have check boxes. Emphysema would be a check and respiratory failure with low oxygen would not be a check.

So I appealed the denial and we will see what happens.