I learned in medical school (1974-79) that white coat hypertension was not clinically important and should not be treated. Somewhere along the line I was also told that people with little variability in their blood pressure fared less well than people whose blood pressure varied according to their circumstances.

As late as 2008, articles were pointing out that awareness of these phenomena could avoid misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment.

White coat hypertension is an important clinical problem given its potential to result in misdiagnosis and possibly inappropriate drug treatment. Although ambulatory and home BP measurements are more accurate and predictive of target organ damage, physicians’ office measurements continue to be the criterion standard. That being the case, the sources of measurement error that occur in the office setting remain an impediment to the accurate diagnosis and treatment of hypertension. Data from several studies show that who takes the BP and how it is taken (ie, by a person or an automated device) have a substantial effect on the measurement.24 Our findings indicate that measurements taken by physicians appear to exacerbate the white coat effect more than other means. We suggest that one way of addressing this problem is to modify the method by which BP is measured in the office setting given the wide availability of reliable and validated automated BP monitors that are suitable for both office and home use. Similarly, home BP monitoring has been shown to predict target organ damage as well as (or better than) ambulatory monitoring25 and, thus, is superior in this regard to traditional office measurements. Thus, BP taken by an automatic device, while the patient is alone in the physician’s office, may provide the best means of avoiding a hypertension misdiagnosis.

— Read on jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/773457

In June of this year, the Annals of Internal Medicine published a widely cited paper that demonstrated that people with white coat hypertension (WCH or WCHT) have up to twice the death rate of people who don’t have it.

“Untreated WCH, but not treated WCE, is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality. Out-of-office BP monitoring is critical in the diagnosis and management of hypertension.”

An old article I found explains that white coat elevations can be transient or sustained and can happen in people with or without hypertension. So what the Annals authors mean by “treated WCE” confuses me. If a white coat elevation is sustained, isn’t that the same as white coat hypertension?

White coat hypertension (WCHT) and white coat effect (WCE) are often thought to be of the same entity. They are in fact different conditions which carry distinctive definitions and prognostic significance. WCHT is diagnosed when office blood pressure (OBP) is ≥140/90 mmHg on at least 3 occasions, while the average daytime or 24-hour blood pressure is <135/85 mmHg. It is common with 15% prevalence in the general population and may account for over 30% of individuals in whom hypertension is diagnosed. Although individuals with WCHT were reported to have a better cardiovascular (CV) prognosis when compared to those with sustained hypertension and masked hypertension; they were also shown to have a greater prevalence of target organ damage (TOD) and metabolic abnormalities than that of normotensive subjects. In contrast, WCE is defined as the transient elevation of OBP induced by the alerting response to a doctor or a nurse. WCE can occur in both normotensive and hypertensive

— Read on www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4170363/

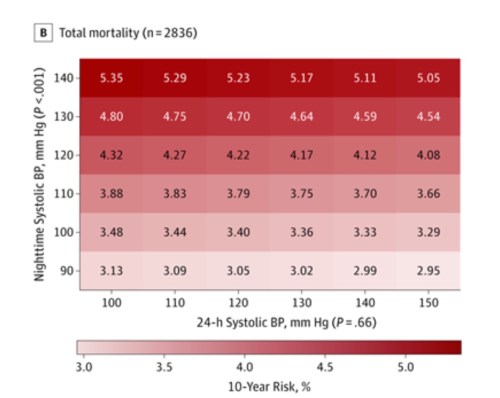

Nevertheless, the most recent piece published on this topic reveals that not only 24 hour measures of blood pressure determine outcomes, but nighttime blood pressure does to the same degree.

“In this population-based cohort study, higher 24-hour and nighttime BP were significantly associated with greater risks of death and a composite cardiovascular outcome, even after adjusting for other office-based or ambulatory blood pressure measurements.“

So, with the possible exception of brief elevations from pain or trauma (I think and hope that still holds true), I guess if we see it, we treat it.

And my clinic just got some ambulatory Blood Pressure monitors…